Yet another story about flighty artisty girl getting married to a staid boring nice guy. The girl cheats on the guy and of course the guy being a good and kind takes it all in stride. And when she comes to her senses, the husband dies of diphtheria, of the nose all things… All I can say is that I was surprised the author didn’t kill off the wife like it was usual in stories in that era of cheating wives. Anna Karennina kills herself. Madame Bovary kills herself. Tess of the Urbanvilles gets hanged, and the like. I suppose that is the point of the story, Chekhov showing his humanist hand by not making the wife dying some terrible death in punishment for her adultery. A shame thought, the husband was the one who got the shaft.

Difficult Times by Anton Chekhov

This story is fairly short and simple. It opens with farmer who has just gained some 300 roubles. His son asks for 15 roubles for his college studies, but the father only agrees to give him 10. THe son, exasperated by his miserliness, leaves in a huff, penniless, determined to never see his family again. But along the way, he runs into a fine lady and she smiles at him, and he smiles back and turns back home. He tells his father off. When he leaves in the morning, the father tells him the money is on table, but it is unclear whether it’s 10 roubles or 15 roubles that the father left for him.

Sometimes the solution to strife is just accepting the terms and parameters of it and moving on. Smile, chin up, and just make a way of it … it’s as simple as that.

The Wife by Anton Chekhov

The premise is fairly straightforward. The narrator is trying to get back into his wife’s graces by offering to help with her charity project, but reconciliation isn’t so simple because the wife has no desire to change their cold war detente state of affairs.

I’m still not sure what to think of this story. The narrator even though dull and self-important and egoistical, clearly loves his wife. And the wife herself … her childish, teary ways grates on me, so I wasn’t so enthusiastic about the narrator’s hope for marital bliss. But the narrator is trying to ameliorate issues, and the wife for whatever reason isn’t accommodating. By story’s end, the narrator concedes to a huge sacrifice, and even then the wife doesn’t budge.

What to say? Perhaps a lesson on the impossibility of communication between the sexes? Or the impossibility of marital bliss? Or that there are some kinds of rift that can never get fixed? Well, who knows …

Bitter Eden by Tatamkhulu Afrika

Whom we love is as much a statement about those whom we reject. In the glut of romantic fiction out there, a lot of books gloss over the rejection inherent in the romantic love because really why do we want to feel sad for the poor sod when there’s a ooey gooey love to gush over. We gloss it over. We find ways to minimize it. Or we turn the rejected character into an asshole, someone who deserved it, a crazy idiot, or worse, an other.

This brings me back to the book I was reading Bitter Eden by Tatamkhulu Afrika. The story is much about pure love as it is about the cruel rejection that made the love possible. Warning, there are spoilers. Actually it’s the whole plot summary. Either way you’re warned.

The narrator Tom is a masculine, single, POW, and by default straight. He first bonds with the married Douglas, who is effeminate and mothering. No one in the prison camp really likes the fragile Douglas. Even the self-identified gay prisoners don’t like him. Tom eventually comes to accept Douglas because underneath his fussy mothering ways, Douglas is loyal and honorable.

After a year of being Douglas’ ‘mate'(all platonic), Tom is more open to his queer side. He’s part of a theatre group run by a gay pow. He regularly submits himself to have his portrait drawn by another gay prisoner who ‘studies his face but draws his genitals.’ Then he runs into another british pow, married Danny, who’s a man’s man and is for all intents and purposes straight. Danny is simply more fun. The bond between Tom and Danny is natural, quick, and goes deeper because they both share wounds of childhood traumas. And oh, Danny can’t stand Douglas in the slightest.

Tom rejects Douglas for Danny. Make no mistake, the rejection is cruel and pure aggression. And you know if Tom hadn’t learnt to accept Douglas, he would not have had the capacity to love Danny. The latter half of book is sweet as much as it is bitter, Tom and Danny blossom albeit in their sly not-overtly sexual way while Douglas goes insane.

Throughout the latter half of the book, Tom grapples with his responsibility in Douglas’ demise. Yes every man is responsible for his own heart, but was the rejection necessary for true love to flower? I kept hoping the men would look beyond myopic delineations of his and mine and use the spark of love to forge something more universal. You know like a brotherhood of sorts, but that wish is a fantasy really. When the death, hunger, torture, stare at you daily, the urge to possess something for yourself only is all that there is.

The rejection speaks to the struggle between the feminine vs the masculine that permeates the whole book, and how being masculine means the rejection of femininity. When Tom decides to play Lady Macbeth, the experience almost breaks their relationship as the pair go to absurd lengths to re-affirm their masculinity. The irony is while Tom is more willing to explore the queerer side of himself and Danny much less so, it’s Danny who wants to continue the relationship after the war ends. But Tom is too afraid. He gets married and doesn’t speak to or hear from Danny again until after his death.

A sad book yes, but a real and touching book. Douglas’ tragic end rings through to the last pages when Tom in his older years is trying to find some resolution to his complicity. Not only did he let Douglas down, he let Danny down big time.

It’s sad how it takes extreme circumstances to discover hidden dimensions of yourself, but as soon as the pressure goes away and the situation returns to the mundane, your expanded horizons shrink back and everything resets to a bland and stifling normal. In the end Tom wishes to go back to the Bitter Eden of the pow camp. The possibility of creating a new Eden in the midst of his homely, freer, normal is not one he seriously grapples with, and that’s just sad.

The year’s literary titles

I thought it would be interesting to study the covers of the debut literary titles this year. I’ll give a shout to the three African writers on this list, Helen Oyeyemi, Teju Cole, who both are of Nigerian Descent, and Dinaw Minegetsu, who’s of Ethiopian descent. And surprise, surprise Larry McMurty, yep that one who wrote Lonesome Dove, is releasing something this year. I had had the impression that he was old and dead already.

Best Cover? The Man who Walked Away. The telescopic arrangement draws your eye.

Terrible looking Covers in my humble opinion:

Harlequin’s Million’s. Oh look my twelve-year-old wrote a book.

The Corpse Exhibition and other stories. Might good on hardback, but looks boring on an ebook cover.

One more thing. The cover artist must have been on vacation that week.

Can’t and Won’t. Forget the cover artist. I can haz type.

Faces in the Crowd. Adding a posted note doesn’t make the non descript picture of a subway interior more interesting.

Pushkin Hills. What could be more exciting than an empty chair and table in the middle of a field? And the icky orange for the font?

Nine rabbits. The cover artist was on pot that week.

An Unnecessary Woman. Looks like an ad for a used book.

Which covers do you like best? Which covers do you like the least?

Don’t forget to click on the covers to see the book descriptions on Amazon.

Don’t forget to click on the covers to see the book descriptions on Amazon.

Kinder than Solitude by Yiyun Li–A Review

Kinder Than Solitude is a book that I received from NetGalley in exchange for my unbiased review. The story opens with the death of Shaiao, whose poisoning led to her lingering in a vegetative state for twenty years before succumbing. The mystery of her poisoning is connected to a group of three Chinese friends, Ruyu, Boyang and Moran.

The book cycles through the three viewpoint characters between the past when Shaoia was alive just around the time of Tiananmen Square Protests and the present immediately after her death. Although the book is labeled a mystery, it isn’t a traditional mystery because no one’s on a quest to solve the mystery. Instead we get the minute to minute ruminations, tedious conversations, angsty wanderings of the three characters. There’s a lot of angst, a lot of sadness and passivity, and the lot of the reasons cannot be excused away lightly due to tragedy or bad circumstances. The reasons are a lot stupider–the characters are simply unable to see beyond the dark prison of themselves for the light of cheer. Yes, the writing is crisp and Yiyun’s observations are piquant and perspicacious, but really the story is joyless little tale of profoundly miserable characters. And in the end the twist on mystery doesn’t save the book from its drudgery, as the culprit is still whom you expected it to be all along.

Every page has a quotable passage, and not the jejune hallmark offerings either, but highlight a penetrating analysis of the human heart. Either way, the preponderance of resonant observation could not save the lot of dialogue from feeling tedious. Every occasion of dialogue turns into the most dreary interrogation because everyone questions everyone else’s motives over the most trivial things. For instance, if someone said hello, the other person would ask, “why are you telling me hello?” the other would reply, “Are you saying there’s something wrong about asking hello?” and on and on they would go.

Why is this book three stars, not two? The writing. Yiyun Li has talent nevertheless that shines on every page, but dear God the characters …. It felt like such a waste.

Still I’d say you should read Kinder Than Solitude because the profundity of Yiyun Li’s writing is worth it.

by Wando Wande

Too Old for Old Tricks–Part One

Happy Easter

It was Easter Sunday. Whatever of life and death, sacrifice and the resurrection were subsumed by the festering jubilation in the grocery store. Buy one get one free rabbit-sized bonbons, seventy percent off honey-glazed ham. Perhaps one could prevision death and its runny afterbirth from the scarlet poinsettias gracing the gardening aisle.

The cold and the diarrheic glimmer of beer bottles billowed from the open-faced fridge before Yinka tightening his arms folded on his chest. His bangles felt icy against the scars on his wrists. Something itched, rather wriggled underneath the squamous scars. Ratcheting the cool metal over his wrists, Yinka regretted the short sleeves of his tshirt and the white hairs over his arms and the infinite choices for beer.

And oh yes, beer. Brown bottle, green bottle. Gold foil cap, slovenly monk with apricot cheeks. Yinka reached for the choice of the past seven years: the case of all-American swill refreshing crisp lager. Bruce preferred it and he preferred to prefer Bruce’s tastes. But he thought, Easter seemed an occasion for something different, something of spring, leastways a resurrection for better beer. And what perhaps of the all-Japanese swill or the all-Chinese swill—How now beer from the middle kingdom of el-cheapos?

And it was decided a case of the house favorite. Then he perambulated the aisles, like a whale that had lost sight of the sea and its obviating vastness, no more content, no less disinclined to feel disappointed in himself for defaulting to the familiar.

Perhaps a different brand of mustard? Bruce bought the mustard. Or the organic, natural, non-fluoride, non-sweetened toothpaste? But the regular one with ingredients of unpronounceables looked less frightening. The soft head brush toothbrush should be better than the medium head toothbrush? Bruce preferred the medium head, but wasn’t the soft head better?

The dental conundrums were no more clearer than the conundrum in his back pocket: a handwritten letter addressed to Bruce Cohn. The letter had arrived three days earlier but Yinka held onto it instead of placing it on Bruce’s study desk like he always did.

And in examining the letter again, feeling the ink strokes mark the white envelope, he decided its precise curlicues and the compact loftiness were of a feminine hand. This ‘Chris Winston’ on the sender’s address must be female, which ruffled him.

Why should Bruce, work-twenty-seven-hours-a-day Bruce, received handwritten letters in this age where sharing and caring were worth less than a byte? Unsurprising given Bruce’s lucky happenstances; still, Yinka held fast, in tremulous wondering, to his own letter addressed to Yinka Peter Olubayo. He would like a letter too. It was just as well Bruce would dismiss his want with a pathetic shrug; and therefore Bruce should not mind if the letter came from a bronzed ephebe lounging on a far-off Greek Island—warm sands and warm bodies. But Bruce would not mind; rather Bruce did not care to mind.

Unnerved, he stuffed the letter back into his pocket and slipped to deliberating between soft head toothbrushes and medium head toothbrushes. Analyses were still as muddy when the loudspeaker bleated the last chance for six inch round lemon chiffon cakes at seven ninety nine. Randomly he tilted his gaze over towards the row cakes on display and was immediately and quietly seized by the fact of the day being Bruce’s birthday. He dumped a pair of medium toothbrushes in his cart and trundled to the bakery section.

The assistant looked young, rudely and flippantly handsome as he played with his tongue in his mouth, rounding cheek to cheek in a careless rhythm. The boy reminded him of rich acorns and fluffy moss. Yinka wanted to reach over the glass display and pop those cheeks. Maybe jump over the display—no, bum knee, bum kidneys—and lay the boy’s face over where his cholesterol-clogged heart was. And he would whisper restfully about hog-tying bucks or practicing the loops of a hangman’s noose—no, none of that—Morse code for SOS or SOB.

Rubbing his wrists mindlessly, he mulled the delicate yellow lemon cake inside a glass shelf.

“Sir, you get an inscription on the cake,” the boy said as if celebration was wanting.

How good of you to call me sir. Yinka suppressed the flutter working up his face. Unearned familiarity was always discomfiting, formality comforting, even subtly arousing from the boy now eying him impatiently. Yinka, looking down, contemplated the crisp frosting flowers on the cake. An inscription might read, “Happy Birthday Bruce, love Yinka,”or rather, “Happy Birthday Emu, many more steaks to you, love Crocky?”

The choices felt dry, wasteful. Bruce’s father was a reformed Jew, his mother a reformed Jehovah’s witness. Birthdays, Easter, the cake being this sop to the crisis of spring, Bruce would not understand it or the pleasures of a handwritten letter.

The blare of the loudspeaker again announced the cheapest unbelievable Easter eggs, and Yinka’s senses whittled away in the disorder murmuring away to eggland. The cake sans inscriptions sounded better, or perhaps just the unfrosted cake, even better to leave off the cake and take home the empty box.

Yinka saw the boy’s fingers uncurl over the glass counter like it was surrendering to the Easter din around. A line of a shadow trailed up the short fingers and its hairs up to the arm and his folded sleeve, and to the face, evidently suffering a gaze on him. He must be new here. Yinka decided not to smile or soften; the boy braved to keep up his stare. His face could be more gentle, could be more innocently boyish. And pink grilled around the temples. The eyes, blue as the twilight, as those myriad eyes that flickered and watched him in his dreams like ghosts roused rudely from stupor.

Yinka hoped the boy was docile as his stance presupposed. He was too tired to fight or boast illustrious feats, much less conquer or claim.

His wrists troubled him again, causing him to fidget with the tight clasps of the bangles. There were inscriptions embossed over the dull metal; inscriptions held no meaning, drove no need in him. And yet casting them aside never occurred to him as possibility.

“Cool bangles,” the attendant interjected.

“You like them?” He regretted his too eager reply and quickly blurted, “Titanium. Made of titanium”

“Titanium? Get out of here.” The boy’s smile was the glitter of clear water. “Now, where does anyone get titanium?”

Yinka saw now the squareness of his hairline, and the mole underneath the brow. The boy could be … Francis, truly? The name had the ring of the faint clink of pebble ricocheting down a well. No face fastened to the name, or smell, or touch. But the name had the surety in his mind, and Yinka concluded it had to be this Francis who gifted him the bangles. But that could not be. Or was it Wilson, his physics Ph.D advisor, who was reprimanded professionally for gross sexual misconduct.

“Must have been someone important,” Yinka said noncommittally.

The boy looked more serious. “You want the cake?”

“Since you insist, I shall.”

“Hehe, doing my best to make more money for the Man,” the boy said. “You want an inscription?”

Yinka chuckled. “Sure. ‘Happy birthday Emu, love Crocky.’”

“Man…” The boy guffawed. “Your name’s really Crocky?”

Yinka looked back at the discolored incisor jutting out of the laughing mouth like misshapen stump. And the puns followed with more laughter and feelings warmed expansively.

“Crocky?” The boy repeated to himself, feeling the size and girth of the word. Then he removed the cake from the shelf and placed it on the counter. He raised sharp eyes to him. “Pink, all right for the inscription … Crocky?”

“Green … if you don’t mind.” Yinka’s voice rose a little. “And you don’t get to call me that.”

“Emu sure can.”

“He stuck around in spite of my balding head. You’d have to give me some of those napoleons for free before I might let you …”

“He —I should get this done.” Cake unsteady in both hands, the boy turned away to the table in the shadowy recesses beyond the light display.

Yinka was amused with how fast his eyes narrowed and his cheeks lost their high mien. But it was all right for dreams to last a moment. A flame that flickered for an instant was no less a flame, after all.

The wrists bothered him impolitely now. They felt as if a hot wire were boring down his wrist and piping up his forearm. Yinka examined the clasps of his bangles, the darker-colored scars underneath, the reticule of thickening veins. Something was clawing from beyond the grave of his youth where names were whispers and faces were chimeras ghosting the deep. Whatever was coming, he did not feel ready.

The boy returned without expression on his face and with the cake yellow, blue and green in a clear container.

“Enjoy,” he said, deadpan.

A tub of ice cream and dishwashing soap, completed the groceries. At the checkout counter, conversation plodded about the involuble weather, paper or plastic, cash or credit, if forty is the new twenty-five.

The cashier’s cheeks were thin and her eyes darkly deep. But there had to be something delightful in her because she smiled and chatted and smiled and chatted a lot. Even though she smelled of earthy mushrooms in the forest damp, Yinka could not help but think of her smiles like lipstick on a skull.

“Forty, wow, I have got five more years till then,” she chimed then defaulted to a careless laugh. “Age is all in the mind. My three-year-old son runs me around all day. I feel old and young at the same time. You get what I mean?”

Yinka nodded, fixed his gaze at the automatic doors, open, close, toddler in a tutu, open, close, man gnashing teeth, in search of coffee. And then the burble on anxieties he was the wrong sex to understand. And of course the son.

“Did I tell you, he put a frog in his mouth the other day.” She clutched her breast. “It scared the bejesus out of me. The last time it was a cricket.”

Yinka thought of the crying, the puling, the mewling of the wobbly things. Those wobbly things were supposed to his lottery ticket to meaning, to immortality. Beautiful things want to beget beautiful things. Good things want to beget good things in the transcriptions of DNA and RNA.

Her words floated on him, floated through him, floated away from him. He was rotating his wrists now to wish away the renascent discomfort.

“You have any?” she asked.

Yinka blinked. “Children? Happily … no.” He pasted a smile then took hold of the handles of the grocery bags. “Here’s to remaining thirty-five forever.”

“Thanks.” Her smile wilting on her lips, she dumped the pair of toothbrushes into the bag. “Wish Bruce happy birthday for me.”

“I shall.” Yinka sighed, moved to lift the bags away, but his wrists hiccupped in pain and the bags dropped with a light bang.

The cashier’s eyes narrowed. “You, Okay there? You need a carry-out?”

“ Thanks, no.” I’m forty-five, not ninety. He gritted his teeth as he jerked the bags off the counter in a show of his lusty strength. The pain was definite, like gears turning in the bones of his wrist. Useless hands. Useless body. Futility was on his mind as he glided from the store to pavement to his car. Inside the car, he refrained from starting the ignition, instead wriggling his fingers and clenching and loosening his fists, trying to feel the strings of pain each action effected. Its prickling sounds lulling him, the wind assaulted dust and pollen upon the windshield and flurried the dry leaves onto oil slicks. He looked at the sky maddeningly bright, maddeningly blue, and waited. For what? For how long? The pain called to pain, his worries called to Bruce.

Gently and precisely, he got his cellphone from his pocket. After a glance at its artic blue screen, he tossed the phone aside and wriggled the letter from his back pocket. It felt warm and damp. There was the graceful name again, ‘Chris Winston’.

Bruce always had truculently asserted his right to identify as bisexual. Yinka dismissed his view as droll; after all seven years of monogamy should decide it one way or another. Yes, but they had had seven year now of what exactly?

His pusillanimous thoughts so appalled him that he flung the letter into the grocery bags on the passenger seat and stuck the keys into the ignition.

“Damn it!” Gently again, he cradled his right hand to himself, but burls of discomfort grew wilder in his forearms and his hand flamed. He could see the red roots curled over his digits, stretched and spiraled over his biceps and clawed its pin tendrils up his wattle. In that great revelation of pain, he lifted his eyes to the eastern horizon. His mind, instantly, expanded, warped, sheared—a great tree darkening half the sky, its leaves of magnesium-blue flame, its fruits hanging like massive lanterns during a Chinese New Year. Today was Easter; rather it was spring, and therefore the season of its pollen celestial tide.

The pollen streamed from the east, covered all over rooftops and electric pole, passed through windows, open hands, open mouths—diamond dust, metaphysical dust enthralled his eyes and prickled his skin. But his hands, the inky roots were bulging and pulsating underneath his taut skin, and neural darts harpooning bursting myriad corpuscles in his brain. Light and its variegated hues bled down his vision, and his arms felt like postulating appendages, the air thick and dry in his nose. And lost in a shattering darkness inside his skull, he slumped onto the steering wheel. Then he remembered.

Francis was not Francis. Wilson was not Wilson. The bangle was simple iron, as old as himself.

Comment! Share! Be sure to tell me what you think!

The subsequent chapters will be password protected. If you wish to read them, please sign up here.

Does Paid Editing Increase Ebook Sales?

WARNING: A LONG ASS POST! You can skip to the take home message at the bottom of the post.

Go to any self-publishing forum. Most of its participants would advise you to have a professional cover and professional editing before publishing. But the reality isn’t so simple.

Traditional publishers usually have s multistage editing process: content edit, developmental edit, line-edit, copyedit, proofreader. Perhaps you’d not recieve all of them, but the last three are crucial. An editor presumably could do all of them, but that’s rare. Usually you’d have 2-3 editors for the entire editing process. Freelance editors quote anywhere from $.005 per word to $.08 per word, content/developmental edits being more expensive. A basic 70,000 word manuscript could easily cost a thousand dollars in editing expenses alone.

Covers costs are more flexible. Costs could be anywhere from $0 or $5 from fiverr, to $20-$40 premades, to $60-$100 Photoshop stock photo manipulations to $200-$500 for high end photo-manipulations to a few thousand dollars if you want original illustrated art that’s usual to the epic fantasy genre. Oh dear, the costs of being professional aren’t trivial.

Are these costs truly necessary in order to produce a book that will sell?

Seems like an easy question to answer, after all we can point to risible covers languishing in the ranks or underperforming books in dire need of edits. However, there are not an insignificant number of ebooks with self-done covers and weak edits selling well enough.

Thankfully Hugh Howey has done the hard task of collecting data that we need. He released groundbreaking report on authors earnings on the Amazon kindle publishing platform. I’d urge you to read it if you haven’t. In conjunction to his study of kindle ebooks, Hugh is running a voluntary survey of book earnings. The survey includes questions about editing and cover choices.

The data is free and available to all. As of this posting, there are 988 responders. If you’ve self-published or trad-published, I urge you to fill out the survey. We’re in crucial need of data to help us understand the self-publishing landscape.

I peeked at the data, actually ran a hacksaw to it. Here are some preliminary thoughts. I’ll look at questions of editing expenses in this post, and on the next post, examine the cover art debate.

A number of caveats first!

With survey data, confirmation bias is KING. Those who make money are likely to respond than those who make nothing. (If you make next to nothing, I urge to fill out the survey). Additionally, there’s a stigma against unprofessional books among serious indies because it’s seen rightly or un-rightly that these books give indie books a bad name. To avoid scrutiny, those who don’t pay for editors or covers are less likely to respond than those who do. And motivated indies are more likely to respond than those who upload a book to Kindle and forget about it.

Besides, people lie or their recollections are imprecise. A indie reported making $13,000,000 in the last year! True or false? A typing mistake? Who knows. Some appeared to have published their first book six months in the future, or some reported income even though they reported publishing zero books. There’s no specificity about fiction/non-fiction, genre or word length or whether the books are in a series.

On a more technical point, the meaning of editing is undefined. Editing could be mean proofreading. Or it could mean a more thorough copy or line edit or developmental edit. I’ll take it to mean that the author paid someone to look through their manuscript in some fashion. ‘Friends and Family’ (F&F) could mean editor friends and family or functionally illiterate friends and family. Which group does beta readers belong to? Among F&F or Critique Groups/Other Authors (CG)?

It’s not uncommon for self-pubbers to publishe a book that is either self-edited or edited for free, and when sales start rolling or presumably when they get bad reviews complaining about the lack of production values, they use the profits to fund a edited version or a more professional cover. Hugh Howey himself has famously said he relied on friends and family to write Wool. His first covers were DIY.

Well then, let’s jump into the data.

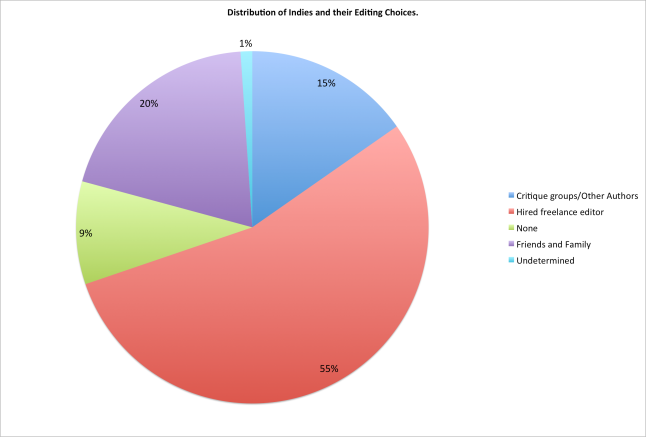

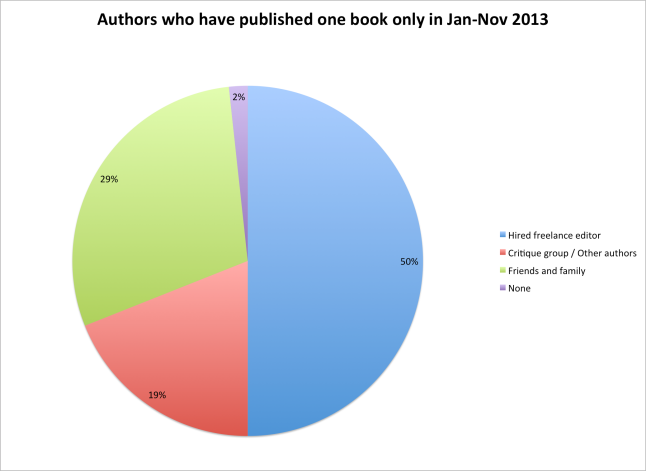

Of the 878 who identify as indie, the pie chart shows the breakdown of their editing decisions. Those marked undetermined did not click a response on the kind of editing they used.

More than half pay for some kind of editing. If the survey is illustrative of self-publishing as a whole, then perhaps the stereotype of entitled wannabes foisting their unedited ‘masterpieces’ upon the masses isn’t very accurate.

How do the past year’s reported earnings compare?

| Average | Median | Max | |

| Critique group / Other authors | $19,104.50 | $725.00 | $1,000,000.00 |

| Friends and family | $21,651.00 | $1,000.00 | $567,000.00 |

| Hired freelance editor | $93,646.70 | $5,250.00 | $13,000,000.00 |

| None | $31,743.60 | $3,000.00 | $1,000,000.00 |

| Undetermined | $2,476.78 | $500.00 | $10,000.00 |

The calculations were done on the total raw earnings of the last year. As expected, those who hired editors did better over all since they have the highest average and median income. But strangely those who relied on CG’s and F&F seemed to be worse off than the self-editers (None Group).

We need to look at the data more closely. For instance, the intrepid self-editer, who reported earning a million dollars, also reported publishing a hundred books! The author who reported 13 million dollars had published 33 books. It’s well known that earnings tend to jump exponentially with each additional books published. Perhaps a large backlist can overcome the purported disadvantages of no-editing.

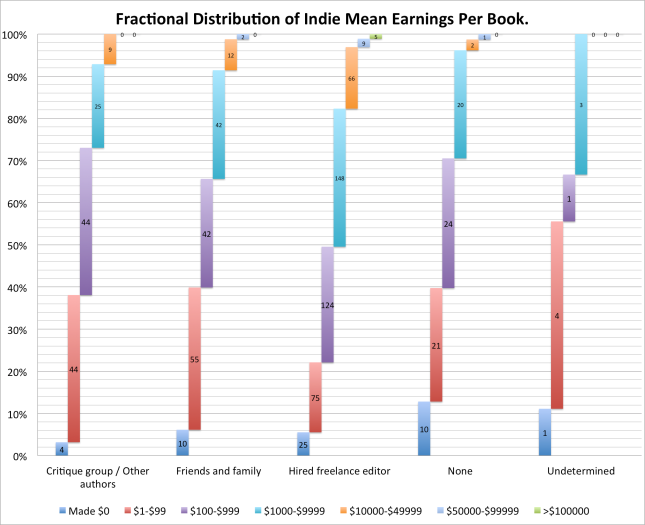

To control for backlist bias, I decided to analyse the mean earnings per books instead of total earnings. The mean earnings per book is the total earnings divided by number of books published. A few data points were spurious because some authors reported income but also reported publishing zero books.

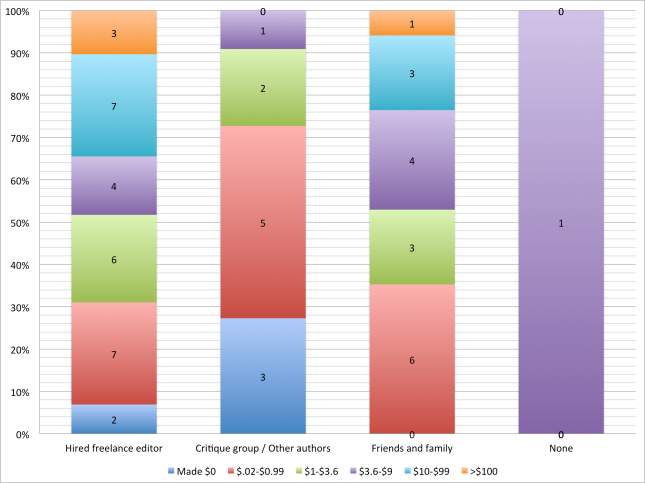

The first $1000 is a good benchmark to study the different groups. Expectedly those who hired editors did the best in that earnings bracket, as 50% of them earned less that $1000 per book. Those who relied on F&F did second best.

Take a look at the CG group and the None group. Surprise, surprise! While the self-editors were more likely to make nothing, they weren’t worse off compared to those who relied on CG’s. 70% of them compared to the 73% of the CG’s made less than $1000. 5% of self-editers made more than $50000 per book compared to the 0% of those who relied on CG’s.

Is the paucity of data to blame for the apparent well being of the self-editers compared to those who relied on CG’s? Probably. Nevertheless, one thing’s certain: authors with varying levels of resources are still able to maximise their potential. Not hiring an editor isn’t the kiss of death.

Are authors earning more because their books have been out longer? Are they writing novels rather than shorts? Are glittering covers the reason for their success? There’s the added fact that after a certain income threshold, time is literally money. It doesn’t pay to edit yourself. Your time is better spent marketing and writing rather than fussing over edits.

Examining mean earnings per book doesn’t quite isolate the legacy of luck, timing, and persistence. And so I decided to look at authors who have published one book only in the last year excluding the month of December. I excluded December because I wanted books with at least a month of earnings. The data cuts down drastically to 58 points, which isn’t much but enough to tinker with.

How about their earnings? I adjusted earnings to take into account the length of time the book has been on the market. In effect, I chose to play with the mean daily earnings instead of total earnings.

8% of those who have hired editors earned zero compared to the 28% of those who relied on CG’s. It would have been nice to see how that compares to those who self-edit, but alas with only one data point, we can’t say anything.

Let’s take a total earnings of $1000 as the benchmark to evaluate results; this translates to 1000/365=$3.6 daily mean earnings. Here, we’re making an assumption that books have daily uniform sales, which is far from true.

Concentrating on the level of the green boxes, we see that those who hired editors and those who relied on F&F came out ahead. Actually they did about the same. 48% of them earned more than $3.6 per day. Those who relied on CG’s did much worse, less than 10% earning over $3.6 a day.

The chart would show that those who relied on F&F did better than those who hired editors, especially so as their earnings are pure profit. But the raw numbers tell a different story. Here are the averages, median and max of mean daily earnings for the different groups.

| Average | Median | Max | |

| Hired freelance editor | $52.38 | $3.14 | $520.83 |

| Critique group / Other authors | $1.15 | $0.37 | $7.03 |

| Friends and family | $14.94 | $3.33 | $109.49 |

| None | $4.00 | $4.00 | $4.00 |

The average author who hired a freelancer earned $52 per day compared to $15 per day earned by the average author who relied on F&F.

By looking at the max earnings, we see that paid editing enables the author to earn a lot more. However, there’s a crucial caveat: To earn that first $1000, editors don’t help much–this we can can see, as half of those who paid editors earned less than $1000 in the last year. Editing costs can easily run over a $1000 for long manuscripts. How long can you stand being in the red?

THE TAKE HOME MESSAGE

Self-editing yea or nay? The self-edited book performs worse than the paid-edited book. AND the book has a greater chance of earning zero dollars. I personally would think twice about self-editing.

You shouldn’t worry too much about hiring an editor either, especially if you’re strapped for resources. You should search high and low for slaves (F&F) to massacre your manuscript. Your earnings potential would be hurt on the top side, but the chart also shows that earnings on the low to medium side doesn’t get massacred either. Moreover, the earnings will be pure profit that can be ploughed back into the book or to make the next book better.

As for relying on critique groups and other authors? The data would confirm what many veterans of writing groups have long suspected. Writerly opinions on your writing might be helpful to learn the rudiments of writing, but not so much when it comes to the book you’re hoping to publish. What writers like to read and what the ordinary readers likes tends to diverge. At some point an aspiring author has to graduate from critique groups to seeking the opinions of those good friends or family who have a vested interest in helping them succeed.

Next post, should you pay for professional covers?

ETA: Ok I see some argumentation from my old folks at Scribophile. I used to be active there, back in the day. Hello!

Those who paid for editing are more motivated to succeed. I have no quibble about that. But I’m more interested in the comparison between those who relied on F&F and those who relied on CG’s and other authors. Who’s the more motivated among the two of them?

Even without more precise data about genre and book length and marketing, it’d seem that those who relied critique groups and other authors aren’t doing all they can to make their book succeed. And yet those who relied on F&F seem to be able to do it.

We’re back to the sticking question. Is the mechanics of critique groups or the writer’s lack of know-how or is it just bad data to blame for the relative lack of performance? I think the data points to something awry about relying on critiques groups and authors, but this is neither here nor there. We can all agree that everyone should try, if they can, to hire editors.

As for the divergent tastes of readers and writers . Let me give an example. Look at the Amazon top 100 fantasy bestseller list. You can tell which books are indie. And their bad reviews tend to be consistent: cliche or juvenile plot, thinly veiled dungeons and dragons campaigns, bad editing. There’s a certain woman who’s making a killing in indie fantasy despite her reviews that ding her for poor editing.

After reading a lot of bad reviews of the indie fantasy bestsellers and those ranked well in the top 5000, it seemed to me that the average indie fantasy reader is easy to please. As long as you tell a good yarn, with clearly drawn tropes, they are fine. The ultra-refined reader who prefers hugo-award winning stories would be appalled that selling authors are still mucking about with the messianic farmboy hero trope. I bet the editors of the pro-paying scifi/fantasy mags would be appalled by what is selling on the top lists.

Writers tend to have more refined tastes because they tend to have read a lot more. They have thought a lot more than the average reader about the mechanics of story and character, prose and style. A common complaint among writers is that they can’t turn off the inner editor when reading published books. They get so snagged with the badly crafted words that they miss the overall story. Readers who aren’t writers tend not to do this. While the unsophisticated reader might not care for cliche or juvenile plots, writers tend to care more. It’s my theory that critique groups can rag a writer too badly for cliches and unoriginality to the detriment of story appeal to the average genre reader.

The Roving Party by Rowan Wilson, a Review.

NetGalley offered The Roving Party in exchange for a review. This book is a literary western with magic realism elements. The story is simple enough. Set in the 1820’s Tasmania or Van Diemen’s Land, a roving party headed by John Batman set out to track and apprehend an aboriginal clan. Central to the story is an aborigine, Black Bill, who aids John in hunting those of his kind.

There isn’t much of a plot or page-turning action or dramatic character development. Instead we’re immersed in the dreary day to day of thugs tracking the “blacks”. Despite the slowness of the plot, the book does engage, mainly because Black Bill is such a mystery. Why would he hunt his own kind? How can he be stoic in the midst of such agressive racism? He is a difficult man to understand, but out of the merry band of thugs, he’s the most compassionate, amazingly enough.

Needless to say, if you’re looking for an easy story to read, this isn’t it. Racism is vicious and ugly and pervasive. Animals are killed without hesitation. Women and children aren’t spared from the cruel calculus of conquest. I didn’t know much about Tasmanian or Australian history before reading this. Oh dear, I know now. Black Bill’s a historical figure, as much as John Batman. They really did go out into the wild looking for aboriginal men to kill, sort of like white men in the American West hunting down Native Americans to kill and scalp–A bit like Blood Meridian, you say?

You’ll find a lot of a reviews that compare this book to Blood Meridian, and the comparison is apt. The prose shares a lot of Cormac McCarthy’s style in cadence, spareness, and emphasis on stark descriptions of the landscape. Dialogue is without punctuation, and the narrative voice exudes poetic omnipotence. However Rowan’s style does leave out McCarthy’s overbearing forcefulness of million-dollar words, paragraph long sentences strung together with ‘and’s, and the unrelenting nihilism of violence. I’m happy to report that Rowan Wilson doesn’t imitate McCarthy’s penchant of taking climatic showdowns off camera.

Ordinarily, this book would earn three stars because I had to make myself read through too many sections of men being inhumane. But the ending surprised me. I think it would surprise you too. The ending only bumps the book from three stars to four stars.

Unflinching and haunting sums it all: The Roving Party.

Cover musings …

I just released a collection of shorts, see here Amazon, Smashwords, Kobo, BN, Google Play. Stories range from fantasy to absurdist tales to somber literary turns, and so it has been especially hard to decide on a good strong image for the cover. I took advantage of the free christmas giveaways of premade covers hosted by the skilled Clarissa Yeo of http://www.bookcoversale.com. I got this below.

A simple cover that probably too staid and doesn’t quite reflect the darkly comic tone of the book, but it gets the job done. But something more dramatic is probably needed to attract more eyeballs to the short story collections. Short stories are notoriously hard to sell on the kindle after all.

I had tried with this cover. Nothing to boast about, but I do like the grumpy look of the duck. I should mention I got that off the flickr, photo credit: http://www.flickr.com/photos/tambako/6128825007/

I was looking through this photoshop tutorial, and I modified it a bit. Ducks came from flickr, photo credit: nezihdurmazlar.com. The castle from nightstock.deviantart.com.

As you can see, making covers are better left to professionals, but it’s fun all the same to play with covers.